- Home

- Language & Culture

- 1A-What is Ngan'gi?

- 1B-Differences between Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri

- 1C-How Ngan'gi is related to other languages.

- 2-Ngan'gi Country

- 3-Ngan'gi Sounds & Writing

- 4-Ngan'gi Verbs

- 5-Serialised Posture Verbs

- 6-Bodypart Nouns inside the Complex Verb

- 7-Noun Case

- 8-Noun Classes

- 9-Ngan'gi Family, Societies & Subsections

- 10-Ngan'gi Kin

- 11-Wangga & Lirrga Song Styles

- 12-A Sample Ngen'giwumirri Story

- 13-Ngan'gi Publications

- Texts

- Audio & Video

- Photos

- Dictionary

- About

10 - NGAN'GI KIN

Ngan’gi Kin

As is true throughout Aboriginal Australia, Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri people place enormous importance on family and relationships. How one person is related to another person to a large extent determines the kind of verbal interaction and other behaviour that takes place between them. On the one hand you find the kind of relationship where ‘acting appropriately’ means general avoidance of deliberate face-to-face interaction. This is most evident between a man and his wife’s mother, so if a man and his mother-in-law realise they are walking towards each other, it would be normal for them to divert to avoid meeting. If a man announces something in camp intended for his mother-in-law’s ears, he’ll broadcast it loudly to ‘no-one in particular’. This kind of avoidance is also widely found in the Daly region between adult brothers and sisters. So if a brother and two sisters travel in a car, it would be normal for the brother to sit in the front and the sisters in the back, just to avoid close proximity and physical contact between sibling of the opposite sex. At the other extreme, you can witness the kind of relationship where ‘acting appropriately’ means ostentatious joking and explicit frequent reference to ‘risque’ topics, as found for example with the ngan’gi wilewile ribald speech style.

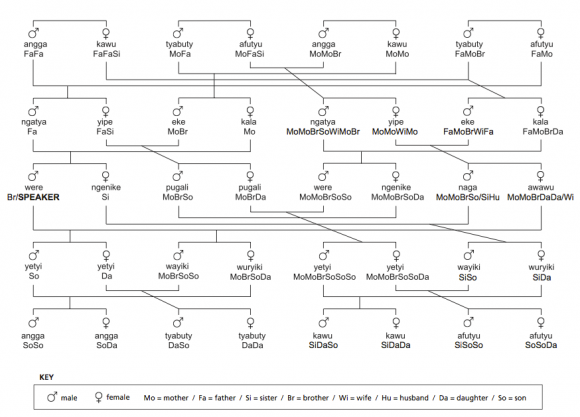

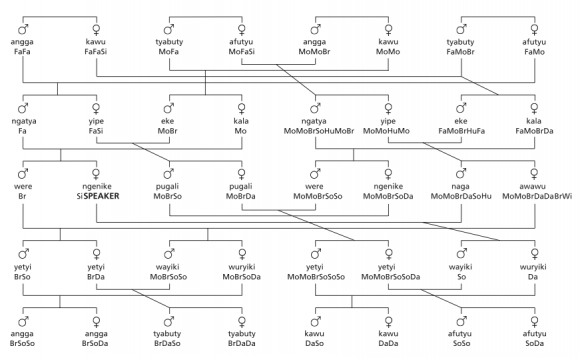

As you might expect in a culture where relationships assume great social significance, in Ngan’gi you’ll find a quite elaborated set of kin term vocabulary, as you can see from the Tables below. English-speaking users of this dictionary will notice immediately that there are some very significant differences to kin terms in English. In Ngan’gi you’ll find examples where a single term picks out a set of people who would be described by differing terms in English – so for example, Ngan’gi kala applies to your mother and also your mother’s sisters. This principle of grouping certain kinds of people together as a ‘set’ is found throughout the Ngan’gi system. So just as your mum and mum’s sisters are referred to the same way, so the children of your mum (ie. your sisters) are referred to by a term that also includes your mum’s sister’s children (which in English would be ‘cousins’ not ‘sisters’). The reverse is also true, so you’ll find Ngan’gi examples where differing terms correspond to a set of people who would be described by a single term in English – so for example, Ngan’gi angga/tyabuty and kawu/afutyu differentiate between paternal and maternal grandparents. You might also notice that the usage of some kin terms depends on the sex of the speakers - so a man speaking Ngan’gi refers to his sons and daughters by different kinterms to those used by a woman speaker.

Invalid Scald ID.

The tables below also capture a further difference to English. Ngan’gi kin terms are based on a 4-generational cycle, such that the terms for 2 generations above the speaker, and 2 generations below the speaker, are the same. Thus your father’s father is your angga, and so is your son’s son.

Ngan’gi Kin System: from the viewpoint of a female speaker

Ngan’gi Kin System: from the viewpoint of a male speaker